By

Gopinath Kumar (PHP Executive Editor)

Sunday, June 27, 2010

Pakistan : Sindh has always been a fertile and rich country. For thousands of years, it had maintained trade links with other countries, some of them in far-flung regions of the world. Historians have found evidence that ships carrying merchandise from Sindh regularly called at the ports of Egypt, Java, China and Sri Lanka. From these countries, goods such as gold and silver ornaments and precious stones found their way to the royal Sindhi courts and temples. Sindh’s government treasuries had always been replete with gems and all types of treasure. In spite of their affluence, Sindhis always avoided to maintain large armies and to conquer the neighboring lands. On the contrary, invaders from outside gravitated to the riches of Sindh attacked the country a number of times and acquired so much wealth by loot and plunder that they dreamed of using that wealth to conquer other countries and extend their sway over the world. This is why all the intruders that have ruled India at times attempted to extend their jurisdiction over Sindh too.

Although we have no coherent accounts of the history of Sindh from the periods prior to the Arab rule, it is an established fact that everyone, from Persian invaders to Alexander the Great, who attempted to conquer India, acquired Sindh too and had a free plunge in the country’s riches. The Arabs wanted Sindh for its wealth to finance their expeditions further deep into India. Al-Hajjaj ibn Yusuf[1] had dispatched his general, Muhammad bin Qasim, with express directions to seize the treasures of Aror and Multan (North Sindh) and occupy all regions of India up to the frontiers of China. Mahmud of Ghazna, the inveterate plunderer, also wanted the treasures of Somnath to finance his Indian expeditions. The principality of Somnath at that time had acquired the status of a regional hub of trade for Sindh and Gujrat. After the conquest of Sindh by the Arabs, Sindhi traders chose to make Somnath their commercial and financial capital, as they considered their wealth more secure in Somnath away from the reach of the Arab marauders who controlled much of the western parts of Sindh. Such was the glitter and allure of the gems and treasure accumulated in Somnath that it tempted Mahmud to descend several times from cold northern valleys beyond the Karakorams thousands of miles down south into the hot tropics of India to quench his lust for pillage and plunder. After a number of attempts and several years Mahmud was finally able to take over Somnath but fortunately by then he was too wearied and too old to further carry on with his nefarious designs and soon after he died.

Zahiruddin Babar too eyed the treasures of Sindh to finance his Indian expeditions. Although Babar did not himself attack Sindh, he extended his reign to Kandhar whose ruler Shah Beg Arghun took refuge in the plains of Sindh and eventually conquered it. It is one of the poignant episodes of the history of Sindh that its enemies at various junctures have put aside their differences and partnered in the exploitation of the country. Shah Beg Arghun after conquering Sindh had Babar’s name chanted in the weekly Juma prayer sermons as the current Muslim Caliph. Although this move legally put Sindh under the suzerainty of Kandhar and effectively made Arghun the deputy or viceroy of Babar, the strategy earned Arghun time to consolidate his hold on Sindh. The Arghun army, after taking possession of the treasures of Sindh, ransacked and despoiled the culturally rich and affluent city of Thatta, and reduced the internationally famed metropolis to a virtual graveyard. When there was nothing left to rob, the army began tearing apart houses to extract timber and other building material. A sizable portion of the wealth thus looted made its way to Kandhar and enabled Babar to raise a large army to attack India and establish the Mughal Empire. There is no denying the fact that Britain could only firm up their control on all of India after they were able to have Sindh. In 1843, when they annexed Sindh, Bahadur Shah Zafar ruled India and just within fourteen years the British forces were able to put a seal on the Mughal rule in India. The economy of Sindh was very important to the British rulers and they at several occasions rejected the demand of the Punjab for more share in the water from the river Indus—although the Punjab was asking for the favor to irrigate the lands that the British government in India had allotted to army men from the province as reward for the latter’s services to the Crown. The British did not choose to disappoint their loyal Punjabi subjects, who had served them through thick and thin and helped them quell every insurgency and revolt, just because they were driven by the values of justice and natural rights. But definitely they were fascinated by Sindh and could not afford to adversely affect Sindh’s revenues and economic output which constituted a sizable portion of the colonial government’s income.

In the present times, the military establishment of Pakistan is dependent on the economic potential of Sindh, which contributes about 70 percent of Pakistan’s GDP. In addition, the country has been exploiting the vast coal, oil and natural gas resources of Sindh for decades. Sindh thus bears the costs of maintaining the 700,000-plus defense establishment of Pakistan and its nuclear arsenal. If Sindh stops injecting funds in the national income of Pakistan, the country would not be able to maintain its military and the Pakistan government would collapse under its own burden. At this stage, it would not be appropriate to segue into a discussion of the raison d’être of maintaining a large military for protecting the borders of any country. It would be just appropriate to note that presently Pakistan army has been made to fight the Taliban and Islamic extremists and embark upon an effort to contain Islamic militancy in the country. In this situation, both the Pakistan army and the Islamic militants need financial resources to be able to keep fighting. The Taliban had seized Swat and adjoining areas not just to have a sanctuary in the tribal belt for themselves but also to take control of the emerald mines and other precious stones quarries in the region. They not only sold emerald extracted from the Swat valley, but they also raised funds by auctioning off the assets of the government and multinational companies in the areas under their control. Before the army launched its operation in the area a few weeks ago, the Taliban held weekly auctions in Swat to sell off the government and multinational assets and traders from all parts of Pakistan, especially the Punjab, participated in those auctions.

Wars, whether fought against insurgents like the Taliban or for conquering the world, incur tremendous costs. To continue waging their so-called Jihad, the Taliban need more than the funds raised by selling the gemstones and war booty. While it can be argued that the primitive and crude Taliban may not be tuned in to the intricacies of economics, but

Pakistan’s establishment is well grounded in the economic realities and are unambiguously aware that how the country earns its income and which part of the country is economically most important. Western countries, particularly the United

States, have time and again voiced their concern that the Taliban enjoy an active and wholesome support of the army and military agencies of Pakistan. These concerns cannot be shrugged off in the face of the fact that Pakistan Army first actively supported and nurtured Afghan Mujahedeen against the Soviet Union and later made those Mujahedeen into the Taliban and kept patronizing them. Like their traditional friends in Pakistan army, the Taliban also know that it is Sindh which keeps infusing blood in the anemic economy of Pakistan. In this backdrop, one can justifiably claim that resettlement in Sindh of the internally displaced persons (IDPs) from Swat is part of a strategic plan to further entrench the colonial-style vested interests in Sindh which have recently been apprehensive of losing out to the new dynamics of globalization in the area. In the light of the symbiotic relation between the army and the Taliban, it would be unrealistic to ignore the thrust of these protagonists to consolidate their hold on Sindh and its resources before the realities of globalization make it difficult for them to unabashedly keep skimming off the surplus Sindh produces. Resettlement of IDPs in Sindh thus emerges as a very clever move: 1. to sustain the Pakistani establishment’s control on the resources of Sindh, 2. to permanently mutilate the Sufi and secular traditions of Sindh and thus extinguish the well-corroborated Sindhi pride that Sindhi youth has always been loath to participate in any type of terrorism. Both the Taliban and Pakistani agencies are adroitly making their moves and this time Sindh happens to be the chess board. According to the leader of Pashtuns in Sindh, Shahi Syed, there are four million Pashtuns in Karachi and nobody is able to make an accurate estimate of the number of the Taliban or members of Al-Qaeda among them. According to estimates, there is a combined population of between seven and eight million Pashtuns in Sindh, which include Afghanis, people from tribal areas, and ordinary Pathans. Although a vast majority of them is settled in Karachi, at least a quarter of this Pashtun population is dispersed in other parts of the province.

Never in history has Sindh suffered so great an influx of outsiders as it has after the creation of Pakistan. First it was the Indian refugees immediately after the Partition in 1947—a vast majority of which was cleverly guided into Sindh and these refugees, who call themselves Mohajirs, kept trickling in for many decades to come. Then it was the notorious One Unit[2] which enabled the Pakistani establishment (the Punjab-dominated civil and military bureaucracy) to settle millions of Punjabis in Sindh. Following the teachings of Machiavelli, the rulers[3] planted pockets of non-native population in various parts of Sindh—in addition to Karachi, there are whole villages and small towns populated by the Punjabi settlers in the interior of Sindh. During the Afghan war in the 1980s, hundreds of thousands of Afghan immigrants made Sindh their permanent home. Now it is the turn of displaced Swatis to head toward the universal sanctuary for the destitute, the displaced and refugees—called Sindh. According to media reports so far about 1.8 million people have been displaced and the town of Swat has been completely abandoned. The problem is not only Swat, the military operation is set to expand to Mingora and the adjoining areas up to Peshawar and the stream of refugees is not going to abate. If most of these IDPs get settled in Sindh, the precarious ethnic balance in Sindh will tilt in favor of the migrants and the Sindhis will be permanently reduced to a minority in their own homeland.

History bears out that whenever Sindhis have been able to self-rule, they have disseminated love and peace and busied themselves in the creation of arts and literature, in cultural activities, in trade and commerce, and, in the process, established and nurtured high civilizations. But whenever Sindh has slipped into the control of outsiders, its wealth has been utilized for regional disruption, war and egotistical pursuits. Because Sindh is the land of Sufis and Sindhis are eternally peace-loving, religious extremism has never endured in Sindh except for intermittent bouts in the times of foreign rule and within the settlements the foreigners established. Sindhis can continue to follow the teachings of the Sufi saints, and conduct themselves as liberal, tolerant, and peace-loving people, only if they will remain in majority in their homeland.

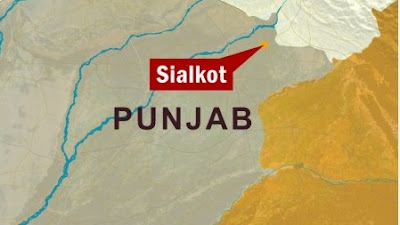

History is full of accounts of migrations and re-settlements, but there has always been a limit to influx of immigrants in a country. One finds no precedence that outside rulers have attempted to resettle their whole towns and cities into their dominions or colonies. The six-decade long state-sponsored resettlement process in Sindh is unique with no parallel anywhere in the world and any time in the history of mankind. The total desertion of Swat in the wake of military operation gives rise to many pertinent questions. Is it sheer failure of Pakistan army or is it part of a well-planned strategy? There are only a few thousand refugees in the camps established by the government and international agencies, while those rendered homeless are estimated at about two million and hundreds of thousands are heading to Sindh! Hordes of them have settled in the districts of Tando Muhammd Khan, Hyderabad, Jamshoro, Dadu, and Karachi and the local Pashtuns in Sindh are receiving the refugees and establishing camps for them. If the Pakistan government is once again up to its old strategy of raking in charity money and stirring the conscience of the world into pumping in more funds in the name of IDPs, the civilized world should not allow themselves to be duped into sacrificing Sindh, Sindhis, and their

5000-year old culture of peace and nonviolence at the altar of this game of strategic compassion contrived by Pakistani agencies. The United States must revisit its current policy and evaluate the causes of past failures in the region. Every time the US took on the Taliban or Islamic militants, the latter slipped out with the help of their inveterate allies in Pakistan army. From Afghanistan the militants infiltrated into Iraq and then into Pakistani tribal areas, and now they are all set to make Sindh their new battleground. In this situation, the United States, instead of wasting time with Pakistan army in the desolate mountains of Swat and tribal areas, ought to concentrate on preventing the influx of IDPs and thus, the Taliban into Sindh, because if Islamic militants get into Sindh, this land of Sufis will turn into an epicenter of talibanization. Sindh can keep its traditions of peace and religious liberalism only if it is able to keep intact the shrines of Sufi saints—both the Hindus and Muslims among Sindhis revere these saints and pay homage to them. The Taliban are notorious for their intolerance toward Sufi saints and they indulged in the shameful acts of destroying Sufi shrines and other symbols of religious tolerance and diversity in Afghanistan. In the absence of these emblems of Sufism in Sindh, there will be mushrooming of madrasahs – churning out multitudes of young talibs ever ready to blow off themselves and everyone else. Pakistan shares borders with India and India has sustained all invasions from the northwest. After the Taliban are able to entrench themselves in Sindh, they will be knocking at the doors of India and their militancy will conveniently spill into India. It may be intentional on the part of those-who-matter in Pakistan, to let India experience the real lightning of Islamic extremism after having them encounter its faint sparks during the Mumbai terror last year. Will it be prudent for the world’s sole super power to let Islamic terrorists broaden the reach of their activities to Sindh and India? The Taliban phenomenon will shatter Indian economy and weaken the country both internally and externally.

Pakistan army which has thrived on enmity with India has contrived this game to circumvent the international pressure that it should focus on its north-western tribal region rather than on its eastern border with India. It appears a calculated move to blur the difference between the army’s new, but unwelcome, enemy and its traditionally favorite foe. The Taliban operating in Sindh will acquire way more strategic importance than their present situation and can nudge China to come open in their support as China considers India its military and economic rival. In that situation, the United States will permanently lose its war against terror. It is in the geostrategic interests of both India and the United States to prevent the influx of the Taliban into Sindh.